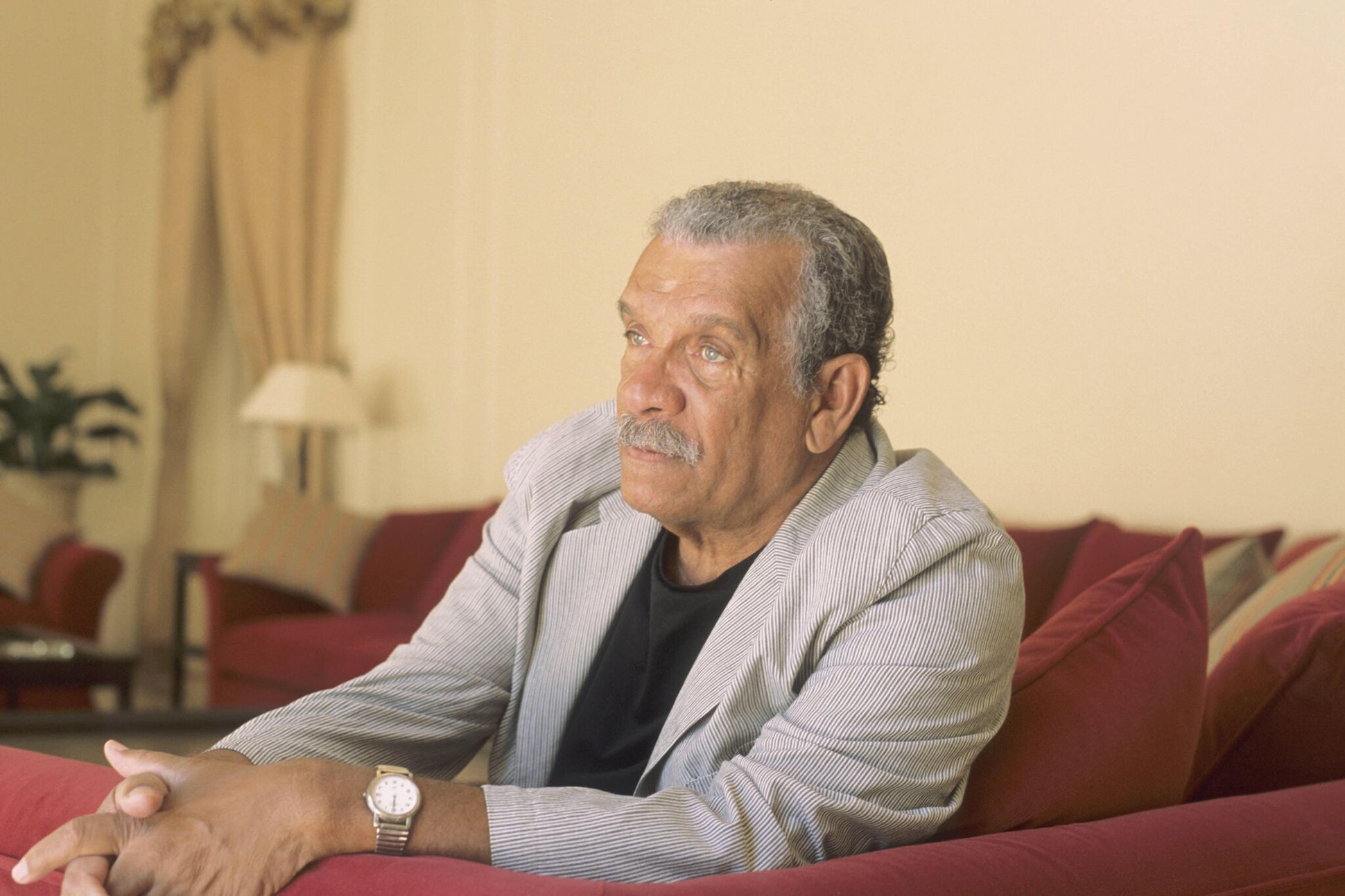

"Born on the island of Saint Lucia, a former British colony in the West Indies, poet and playwright Derek Walcott was trained as a painter but turned to writing as a young man. He published his first poem in the local newspaper at the age of 14. Five years later, he borrowed $200 to print his first collection, 25 Poems, which he distributed on street corners. Walcott’s major breakthrough came with the collection In a Green Night: Poems 1948-1960 (1962), a book which celebrates the Caribbean and its history as well as investigates the scars of colonialism and post-colonialism. Throughout a long and distinguished career, Walcott returned to those same themes of language, power, and place. His later collections include Tiepolo’s Hound (2000), The Prodigal (2004), Selected Poems (2007), White Egrets (2010), and Morning, Paramin (2016). In 1992, Walcott won the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Nobel committee described his work as “a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment.”

Since the 1950s Walcott divided his time between Boston, New York, and Saint Lucia. His work resonates with Western canon and Island influences, sometimes even shifting between Caribbean patois and English, and often addressing his English and West Indian ancestry. According to Los Angeles Times Book Review contributor Arthur Vogelsang, “These continuing polarities shoot an electricity to each other which is questioning and beautiful and which helps form a vision altogether Caribbean and international, personal (him to you, you to him), independent, and essential for readers of contemporary literature on all the continents.” Known for his technical control, erudition, and large canvases, Walcott was, according to poet and critic Sean O’Brien, “one of the handful of poets currently at work in English who are capable of making a convincing attempt to write an epic … His work is conceived on an oceanic scale and one of its fundamental concerns is to give an account of the simultaneous unity and division created by the ocean and by human dealings with it.”

Many readers and critics point to Omeros (1990), an epic poem reimagining the Trojan War as a Caribbean fishermen’s fight, as Walcott’s major achievement. The book is “an effort to touch every aspect of Caribbean experience,” according to O’Brien who also described it as an ars poetica, concerned “with art itself—its meaning and importance and the nature of an artistic vocation.” In reviewing Walcott’s Selected Poems (2007), poet Glyn Maxwell ascribes Walcott’s power as a poet not so much to his themes as to his ear: “The verse is constantly trembling with a sense of the body in time, the self slung across metre, whether metre is steps, or nights, or breath, whether lines are days, or years, or tides.”

Walcott was also a renowned playwright. In 1971 he won an Obie Award for his play Dream on Monkey Mountain, which the New Yorker described as “a poem in dramatic form.” Walcott’s plays generally treat aspects of the West Indian experience, often dealing with the socio-political and epistemological implications of post-colonialism and drawing upon various forms such as the fable, allegory, folk, and morality play. With his twin brother, he cofounded the Trinidad Theater Workshop in 1950; in 1981, while teaching at Boston University, he founded the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre. He also taught at Columbia University, Yale University, Rutgers University, and Essex University in England.

In addition to his Nobel Prize, Walcott’s honors included a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award, a Royal Society of Literature Award, and, in 1988, the Queen’s Medal for Poetry. He was an honorary member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. He died in 2017." from Poetry Foundation

from Omeros

BY DEREK WALCOTT

BOOK SIX

Chapter XLIV

I

In hill-towns, from San Fernando to Mayagüez,

the same sunrise stirred the feathered lances of cane

down the archipelago’s highways. The first breeze

rattled the spears and their noise was like distant rain

marching down from the hills, like a shell at your ears.

In the cool asphalt Sundays of the Antilles

the light brought the bitter history of sugar

across the squared fields, heightening towards harvest,

to the bleached flags of the Indian diaspora.

The drizzling light blew across the savannah

darkening the racehorses’ hides; mist slowly erased

the royal palms on the crests of the hills and the

hills themselves. The brown patches the horses had grazed

shone as wet as their hides. A skittish stallion

jerked at his bridle, marble-eyed at the thunder

muffling the hills, but the groom was drawing him in

like a fisherman, wrapping the slack line under

one fist, then with the other tightening the rein

and narrowing the circle. The sky cracked asunder

and a forked tree flashed, and suddenly that black rain

which can lose an entire archipelago

in broad daylight was pouring tin nails on the roof,

hammering the balcony. I closed the French window,

and thought of the horses in their stalls with one hoof

tilted, watching the ropes of rain. I lay in bed

with current gone from the bed-lamp and heard the roar

of wind shaking the windows, and I remembered

Achille on his own mattress and desperate Hector

trying to save his canoe, I thought of Helen

as my island lost in the haze, and I was sure

I’d never see her again. All of a sudden

the rain stopped and I heard the sluicing of water

down the guttering. I opened the window when

the sun came out. It replaced the tiny brooms

of palms on the ridges. On the red galvanized

roof of the paddock, the wet sparkled, then the grooms

led the horses over the new grass and exercised

them again, and there was a different brightness

in everything, in the leaves, in the horses’ eyes.